Policymakers working to advance extended producer responsibility bills should more deliberately consider climate change mitigation strategies when crafting legislation, according to a white paper from the West Coast Climate and Materials Management Forum’s EPR working group.

Explicitly designing EPR policies with measurable ways of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, as well as prioritizing waste prevention and reuse and requiring transparent environmental impact disclosures, can help bring EPR policies more in line with climate change goals, it said.

Though EPR has the potential to positively impact the environment, it isn’t always a climate change strategy on its own, said forum members, who represent state, local and tribal governments. The white paper suggests policymakers “go beyond recycling for a more comprehensive approach to reducing the environmental impacts of packaging.”

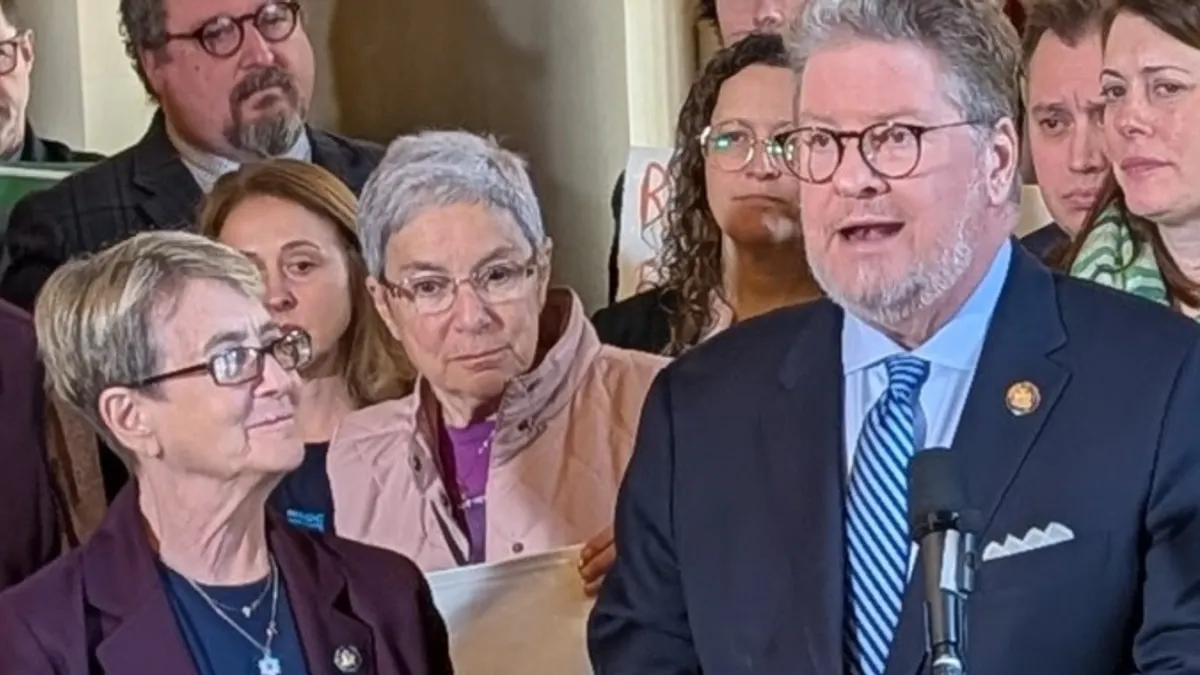

Interest in EPR legislation has been growing in the last few years, alongside the public’s greater understanding of packaging waste and the climate change crisis. However, “the response we're seeing to the packaging problem isn't necessarily optimized from a climate perspective,” said David Allaway, a senior policy analyst at Oregon Department of Environmental Quality and a member of the forum’s leadership team. “It seems more organized around goals of landfill avoidance or cost shifting, and people are attributing potential environmental benefits and climate benefits to it.”

The white paper suggests several strategies to bring the two efforts together. For example, EPR bills could require producer responsibility organizations to fund waste prevention and reuse programs, which is something Oregon has baked into its own EPR law by requiring up to 10% of collected funds to go to such programs. EPR bills in both Illinois and New York also proposed a waste prevention and reuse fee, Allaway said. Illinois passed an EPR study bill this year, while New York’s EPR bill failed to pass.

The white paper recommends distributing funds through a public entity rather than PROs “for optimum effectiveness and public benefit.” Clear goals and metrics for waste reduction are also important, it said.

The U.S. EPA’s waste management hierarchy and food waste hierarchy both make waste prevention and source reduction the top priority. The forum echoes that recommendation, saying waste reduction at the source “often results in greater reductions in greenhouse gas emissions than recycling or composting the same material at end-of-life.” It cites an EPA statistic that 42% of all domestic GHGs come from the production, transportation and disposal of materials and products. Since most of these emissions happen “upstream” of consumers, they cannot be reduced through recycling alone, it says.

Reuse strategies can also offer GHG reduction benefits, but the report cautions that those benefits may depend on how reuse programs are implemented. In some cases, a particular reuse program might contribute more to greenhouse gas emissions. “Depending on the type of material and what it is replacing, the benefits of reusables may hinge on such variables as washing, transportation, and loss rates of reusable items,” the report said.

EPR policies that require PROs to evaluate and disclose the environmental impacts of their products could also help address broader climate change factors, the report said. One way to do that is through eco-modulation, or providing financial incentives for companies in the PRO to pay lower fees when their covered packaging is more environmentally friendly. Such policies must also determine clear metrics for measuring a product’s carbon impact, such as through a life cycle assessment.

EPR policies must also make clear that most kinds of recycling and composting are critical to battling climate change, but “not all recycling is equally environmentally beneficial, [and] some recycling activities have the potential of increasing GHG emissions,” it states.

For example, drop-off recycling locations might generate more GHGs than are offset by the recycling process because it requires residents to use personal vehicles to drive themselves to the locations, it said. In the case of glass recycling, the process of crushing bottles for use in cement might consume less energy than the process of turning them into new bottles — but using the material for cement may not be considered “recycling” for the purposes of local laws, it said.

Crafting a strong EPR policy that balances recycling goals with GHG reductions can be a challenge. “Optimizing the recycling system to achieve the greatest reduction in GHG emissions is not the same as maximizing recycling rates or aiming to recycle or compost all materials,” the report states.

The forum’s EPR working group published a version of the white paper last year, and the group recently updated it to add numerous pages of footnotes and sources with additional data, Allaway said. “The goal here is to put these ideas in front of people who are developing policies and give more proverbial arrows in their quiver, as they try to figure out how to deal with climate change.”

Interested in more recycling in news? Sign up for Waste Dive’s weekly Recycling newsletter here.