The ’90s are back, and so is some of its technology. Invented in 1994, the QR code is enjoying a second life in the United States, particularly across food, drink and consumer goods packaging.

“There was a time where everybody was like, ‘Oh, the QR code is dead,’” said Gena Morgan, the vice president of global standards at GS1 US, the industry-backed nonprofit for standards such as the Universal Product Code barcode. “And then came COVID.”

In 2020, 70.6 million smartphone users in the U.S. scanned quick response codes, according to Statista, a number that jumped to 88.9 million by 2022 and is expected to surpass 100 million by 2025. Of shoppers who used marketing QR codes as of June 2021, over half were between the ages of 18 and 29.

The consumer packaged goods industry sees the QR code resurgence as an opportunity to engage with customers even further. As plans to expand and codify the use of QR codes on packaging continue, brands will have to pay attention to when, where and if consumers stay interested in the technology.

A pandemic push

QR codes, originally made by the Toyota subsidiary Denso Wave to track car components during assembly, started gaining ground in the U.S. in the 2010s — Snapchat, for example, introduced the tech in 2015 — but most instances required smartphone owners to download an app to read the black and white squares. As one 2015 study of QR code habits among Cal Poly Pomona students phrased it, “the rate of adoption for QR codes has not been stellar among smartphone users overall.”

Today, not all people in the U.S. have the ability to interact with QR codes. Though federal nutrition programs or Medicaid may provide some enrollees with smartphones, 15% of people in the U.S. lack the devices, including higher percentages of seniors and low-income individuals. Those with Android and Apple phone cameras, however, can scan QR codes without another app and the codes have become common for other uses, like restaurant menus or COVID-19 vaccination verification.

The renewed familiarity with QR codes has encouraged brands and retailers to reincorporate the tech as a communication tool.

Brands connect whatever website they want to the codes, sending shoppers to a seemingly infinite number of resources. The information density of QR codes also leaves more room on the package itself for mandatory disclosures or brand designs. And because the destination website can be modified any time, manufacturers can rely on QR codes to share updates, like whether the product has been recalled. Access to the same packaging information in customized font sizes, screen brightness, or audio versions could also make product details more accessible for a wide range of shoppers.

Recent announcements of new brand QR code programs have ranged from Cornbread Hemp offering QR codes on each CBD package linking to a third-party lab report, to certain Miller High Life packaging with QR codes that enter participants into a sweepstakes. Both programs align with the two general categories of QR code destinations that companies seem to gravitate toward, said Morgan: further product information and programs to build brand loyalty.

Picking tactics

For brands using QR codes to provide extra context about their projects, another industry organization has developed a standard QR code landing page. SmartLabel, launched by the Consumer Brands Association in 2015, offers shoppers a series of tabs such as nutrition information, ingredients and genetically modified organism status. The design focuses on giving shoppers a reliable result whenever they scan a code.

“The goal is that consumers have the exact same experience, regardless of what brand they're shopping for,” said Rishi Banerjee, senior director of SmartLabel at CBA.

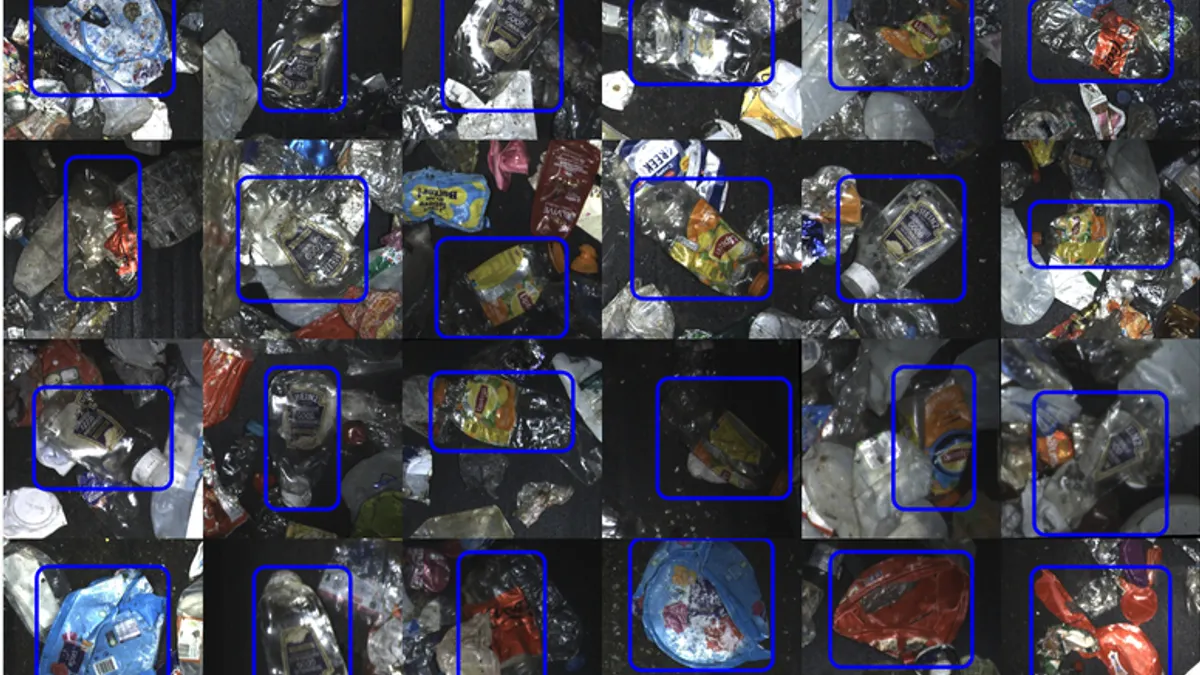

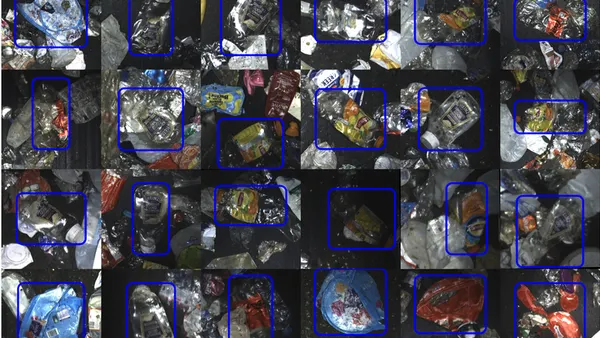

Over 1,000 brands and 100,000 individual products participate in SmartLabel, which continues to debut new features. While brands have been able to include more generic recycling information in their SmartLabel tabs, as of recently they can tap into a new program by The Recycling Partnership called Recycle Check that lets consumers scan a QR code and enter their zip code to learn local recycling guidelines for that product. Recycle Check can exist as a standalone QR code on a product or be integrated into SmartLabel offerings. “As we roll out more dynamic use cases, we do expect consumers to scan more,” Banerjee said.

Surveys suggest this kind of product information would draw in shoppers. In a 2021 questionnaire that research firm Forrester offered to 322 adults familiar with using QR codes, 40% said they would use them to make “smart purchase decisions” in the grocery store. Over half of the respondents said they would use QR codes to redeem coupons or promotions while shopping.

Not every promotional program will entice shoppers to interact with QR codes. In a recent study on the Cornell University campus, food and agricultural economist and assistant professor Aaron Adalja and his colleagues worked QR codes into the labels of milk sold in a school-run store. For the first four weeks, half the milk had a visible sell-by date and a QR code that showed the same sell-by information. In the second four weeks, half the milk only showed the price and expiration date — along with a discount depending on how soon the milk should be purchased — via QR code.

While 70% of the milk sold in the first half of the study had a QR code, only 52% of sales in the latter four weeks were of QR code containers. Interest in the QR codes dropped, even though the second phase offered shoppers some possible savings. For all eight weeks, there were more sales of QR-labeled containers than there were scans of the codes themselves.

Adalja and his team have some ideas about why QR popularity declined. “Our one big hypothesis is that it’s kind of a hassle,” Adalja said. Maybe for bigger-ticket items, like steaks, shoppers would be interested in scanning different options for a discount. But in the case of half-gallons of milk, it seems the novelty of the QR codes or consumers’ willingness to access their information — possibly a combination of the two — lessened over time.

The results align with some standard knowledge about customer engagement, Adalja said. “This isn’t new, but it’s king. If you introduce tech that erodes convenience, it’s likely to kind of backfire on you.”

Generally, he said, a product modification will be more successful if it maintains or improves accessibility to information. For example, a QR code sending people to a recipe that they would otherwise read off the container might have more lasting popularity.

Looking ahead

As QR codes evolve, brands will have to pay attention to packaging laws and what kind of information local or federal governments require to be visible on the item itself. Since individual states make a range of labeling laws, such as product date label requirements, brands have to meet a patchwork of mandates, Adalja added.

In January 2022, new U.S. Department of Agriculture rules kicked in requiring brands to disclose whether or not food have been “bioengineered” with genetically-modified ingredients, with QR codes included as one approved communication method. In another example, brands selling cleaning products in California have had to disclose certain ingredients on the label since 2017. Though Banerjee said some manufacturers might choose to offer the same information via QR code if they can elaborate on why those ingredients are there.

Plans to embed QR codes in the checkout process as an alternative to UPC barcodes could also expand the number of products on shelves with a black-and-white brand portal.

In an initiative called Sunrise 2027, GS1 would like to help all retailers have the technology to scan 2D barcodes — a category of labels that includes QR codes — by 2027. While the program won’t phase out UPCs the intent is to encourage brands to merge the typical bars of vertical lines with 2D barcodes. That way, shoppers can access brand or retailer content affiliated with the code depending on how they scan it, and retailers can rely on the same graphic at the point of sale. Bitly, a 2D code generator company, recently announced plans to funnel more resources into GS1 standards for connecting QR codes on consumer products to websites.

The other type of 2D barcode that brands might adopt is called a data matrix. Morgan said that GS1 is betting the QR code will be more popular, as it holds more data, is more familiar to customers and is easier for digital devices to read.

And even if consumer interest in QR codes in other settings is waning — tracking of restaurant menu QR use shows diners are less interested in ordering that way than they were two years ago — consumer product brands think that QR codes are the answer to shoppers’ demands.

“Consumers are more interested in transparency, industry is more able and willing to share product information, and there's a great tool that everyone knows how to use,” Banerjee said. “It seems like the perfect storm.”