Hammont Premier Packaging didn’t wait until the Trump administration’s tariff announcements this year to rethink its supply chain. The small New Jersey-based company, which sells clear boxes, bags and more, started diversifying sourcing and onboarding additional suppliers in North America and Europe more than 18 months ago.

Hammont realized that “substrates imported from Asia, especially China, tend to be more susceptible to tariffs and logistical slowdowns,” CEO Isaac Link explained. In some instances, the company invested in local suppliers or redesigned products to reduce reliance on materials made only in China.

“The current climate demands flexibility,” Link said.

Shifting trade policy, frequent changes to tariffs and evolving legal challenges have created uncertainty for packaging companies, along with their customers and suppliers. Earlier this month, the U.S. and China agreed to a 90-day pause on higher tariffs, but relations remain uncertain. Meanwhile, tariffs on key trading partners such as Canada and Mexico have shaken supply chains, especially for businesses that started to diversify away from Asia to North America during the pandemic.

Although certain increased tariffs have only been in place a few months, “the impact is already showing up in subtle but serious ways,” said Jennifer Dochstader, co-founder of LPC Inc., a marketing and research consultancy specializing in the global printing and packaging industry.

One example would be a brand that delays its product launch or rebrand because of tariff-related price hikes, she said.

“The ripple effect hits the flexible packaging printer, the label printer, the folding carton producer, the co-packer,” Dochstader said.

Tariffs and their effects on packaging supply chains have caused widespread uncertainty. Here are five questions packaging businesses face while navigating next steps.

How do tariffs affect the packaging industry?

The most immediate impact is cost.

Adam Peek, founder of Golden Rule Consulting and the People of Packaging Podcast, said a commercial printer that buys paper from Canada suddenly experienced skyrocketing costs for the largest item it sources. But the tariffs could be rolled back as quickly as they were enacted, Peek said, making it challenging for the packaging company to decide how to mitigate cost increases.

“The uncertainty in tariffs is creating a lot of stress and tension in the supply chain,” Peek said.

During spring earnings calls, Smurfit Westrock noted shifting some production among sites in Canada and the U.S., and Packaging Corporation of America noted that trade uncertainty led it to adjust some exports.

But many large packaging companies reported minimal anticipated effect from tariffs due to low exposure and domestic supply chains. In early May, Sealed Air noted most of its products aren’t affected by tariffs because of an exemption for goods covered by the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement. And O-I Glass said just 4.5% of its global sales volume is exposed to new tariffs, mostly related to imports of filled containers from Europe.

Ardagh Metal Packaging’s North America can-making operations are all in the U.S., and its “suppliers, customers and end consumers are all mostly local to the region,” CEO Oliver Graham said.

Even in domestic packaging supply chains, knock-on effects of tariffs are still a possibility, said Anish Thanatil, North America lead for Boston Consulting Group’s forestry, pulp, paper and packaging work. If consumer demand shrinks due to higher prices, packaging producers will feel the ripple effects up the supply chain. Or if companies need to purchase equipment to add more paper manufacturing capacity, machinery and parts may be subject to tariffs.

“Everything that's made in the U.S., in some way, is going to be impacted by tariffs,” Peek said. “We've built a global economy.”

Is the industry prepared to handle shifting trade policy?

Packaging leaders have managed their supply chains through disruptive times over the last decade. Tariffs enacted during the first Trump administration pushed many businesses across industries to diversify their sources of supply. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic imparted similar lessons about diversification and holding buffer inventory.

“We learned a lot during the COVID pandemic on how to navigate through the unknown and the chaos,” Peek said. “Being single-sourced as a company for critical packaging components is maybe not the best idea.”

Many companies started to more actively understand the risks in their supply chain during that time, according to Thanatil.

He added that many firms have a playbook so they can refer back to how they managed supply chains during COVID and use those same strategies today. But the current tariff situation bears some key differences.

“In COVID, you knew that you had to plan for at least a year or two. Here, we don't know the timeline,” Thanatil said. “People are more prepared than they were during the pandemic, but there's also more uncertainty.”

Are packaging companies and CPGs making changes?

Multiple companies have discussed the potential to alter packaging substrates or formats in light of tariff-driven supply chain changes.

P&G plans to look “for every opportunity to mitigate the impact, including sourcing flexibility and productivity improvements,” along with price hikes for consumers, CFO Andre Schulten said on an April earnings call, before the 90-day tariff pause with China began. Schulten said P&G’s largest tariff impacts come from raw materials, as well as packaging materials and finished products sourced from China.

Last month, Hammont switched the color of one of its paper bags from a medium brown shade made in China to a darker shade available in India, Link said.

But for the most part, packaging manufacturers are holding off on major changes to materials and formats until they have a better sense of the longevity of the tariff situation.

“There’s a lot of wait-and-see energy right now,” Dochstader said.

Transitioning substrates is not a quick and easy choice for packaging firms nor their customers, Thanatil said. He gave the example of a company that’s considering switching from a tin can to paper, because most tinplate is sourced globally while paper for food cans is produced domestically. A CPG would need to test the material and possibly install new manufacturing lines to fill the new can type – none of which can happen in the short time frame in which the U.S. is imposing tariffs.

For that reason, Thanatil projects that major shifts in substrates or formats are “on a back burner” for two to three months as businesses await the possibility of greater clarity.

Which materials and substrates are most (and least) exposed?

Metal is among the packaging materials most vulnerable to geopolitical shifts. Two-thirds of metal for food packaging in the U.S. is imported, and most tinplate capacity has been shut down in the U.S., Thanatil said.

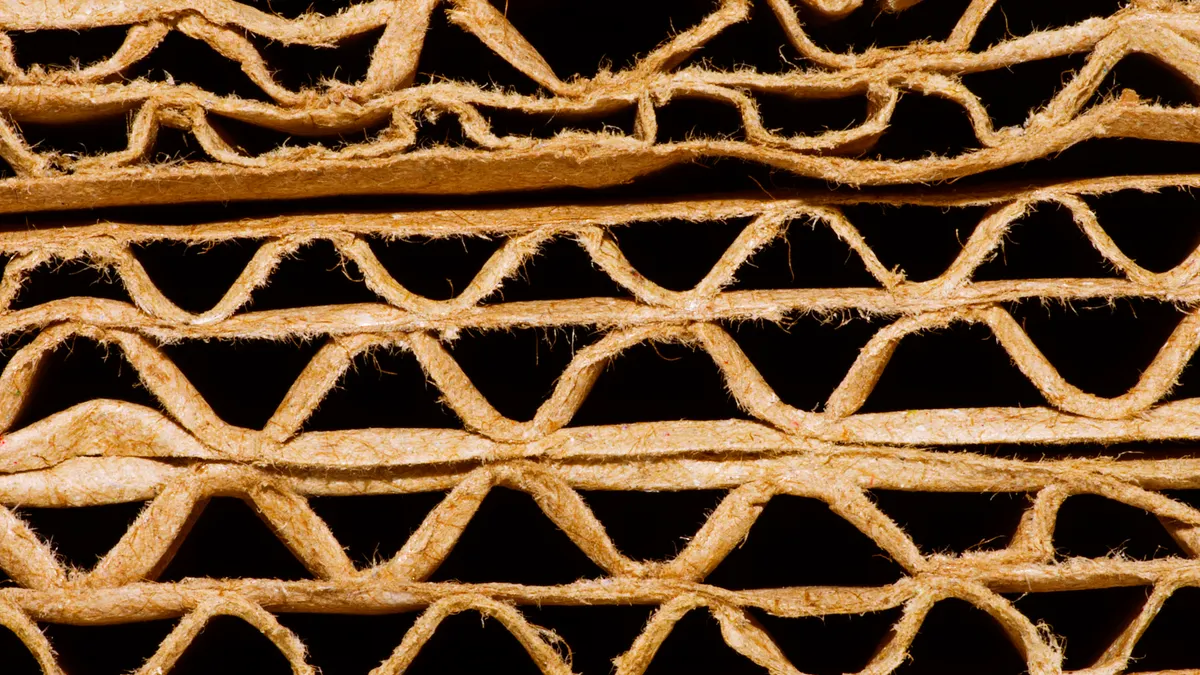

Conversely, flexible and rigid plastics, along with paper, are at an advantage because of their domestic supply chains, Thanatil said.

In many cases, products are manufactured in one place but packaged in another, exposing the goods to tariffs. Many CPGs import raw materials and then manufacture or package domestically, Dochstader said. In the case of electronics, products are manufactured overseas, so the packaging is produced in the same region.

“We're not going to make packaging here for iPhones and then ship it to China. That would be ridiculous,” Peek said.

Clorox noted its tariff exposure is “relatively limited” because “we tend to manufacture closely to where we sell our products,” CFO Luc Bellet said on a May earnings call. But he added that most of the tariff impact is on packaging and raw supplies.

What should packaging execs focus on right now?

Because the tariff situation remains fluid, experts advised working to make supply chains more resilient, while focusing on long-term packaging trends.

For example, younger generations show preferences toward sustainable packaging and healthier eating, Thanatil said. Making a packaging change that results in lower exposure to tariffs but doesn’t align with sustainability goals may not be a worthwhile tradeoff.

Diversifying suppliers, reshoring production and reengineering designs are all possibilities to make the supply chain better able to absorb shocks.

“If you're a procurement person, you have to be willing to entertain new potential opportunities,” Peek said.

He emphasized that doesn’t mean moving all orders over to the vendor with the least tariff exposure. In fact, now is the time to strengthen long-term vendor relationships, not abandon suppliers if they raise prices, sources said.

“They’re reacting to cost pressures of their own,” Dochstader said. She advised that companies ask their vendors questions to clarify what’s driving pricing and to consider design tweaks or lower minimum order quantities.

Link said that when Hammont rolls out “unavoidable price hikes,” it does so with advanced warning. And it will honor old pricing until the company and its customer agree on a date for the new pricing, even if it comes at a cost to Hammont.

“Everyone is in the same boat here just waiting for this to pass,” Link said.

Open communication is important on the customer side, too. Packaging companies sometimes keep supplier information close to the vest with vague specifications so customers can’t seek alternative quotes.

“That veil has to be ripped to just create ultimate transparency and communication with your customers,” Peek said. “That's how you'll navigate through everything in a world that's hard to navigate right now.”

Peek advised packaging executives to stay informed on changing trade policies, but cut through the noise by focusing on what they know is true — and use that to guide decision-making.

“You're not going to disrupt your entire supply chain just because there's a tariff policy in place this week that could change next week,” Peek said.